By Earl Thansonbeed

PANGNIRTUNG, Canada • October 14, 1976 — Rick Sylvester, a stuntman on the last six James Bond films, watched the monitor and shook his head.

“I don’t know how we’re supposed to ski like him. He looks like he’s taking a shit with goggles on,” Sylvester said. “The guy doesn’t deserve to look as great as this jump will make him look. He’s phoning it in.”

Alan Hume, the second unit cinematographer, sipped his Harvey Wallbanger. “Remember, Ricky, you’re doing this stunt for Her Majesty. Not for Roger Moore.”

The crew for “The Spy Who Loved Me” — cameramen, helicopter pilots, doctors, and stuntmen — was huddled around a space heater next to a bar cart at the base of Mt. Asgard. Over the last few days, as they waited for the weather to clear, they’d dubbed their makeshift bar Bitmoore’s. The second unit crew had flown into the Northwest Territories, 20 miles north of the Arctic Circle, a week earlier after a month of filming in Sardinia, where Moore had been particularly awful.

Base Camp

1 ½ ounces bourbon

¼ ounces Islay Scotch

¼ ounces creme de cacao

¼ ounces allspice dram

2 dashes orange bitters

Stir all ingredients with ice • Pour over a large ice cube in a rocks glass • Garnish with a lemon peel

“Spy” would be Moore’s third Bond outing, and he was acting like a star. In Sardinia, he’d required 57 takes for a scene that had him dropping a fish out the window of Bond’s Lotus Esprit S1 submarine car as it drove out of the surf onto a beach packed with surprised Italians.

In dozens of the submarine car takes, he couldn’t stop yawning as the car drove out of the sea and onto the sand. In others, he was reading How to Be Your Own Best Friend as the car emerged from the water. Director Lewis Gilbert was constantly pleading with the actor between takes: “A bit more, Roger?” Hence the name of the makeshift basecamp bar at Mt. Asgard.

Hume and Sylvester studied the skiing moves Moore had filmed in front of a green screen months earlier at Pinewood Studios in London, hoping Sylvester could emulate his style. As the crew drank shots of Canadian Club and reviewed the stunt's logistics, Moore walked into Bitmoore’s carrying a suitcase. No one actually groaned, but everyone groaned.

Editor’s Note:

Dear DCH reader, we apologize for the extended period between our not-real cocktail origin stories. Our publisher was working on a different project and demanded that we pause publication of DCH until it was complete. Happily, it finally is, and we can return to making stuff up.

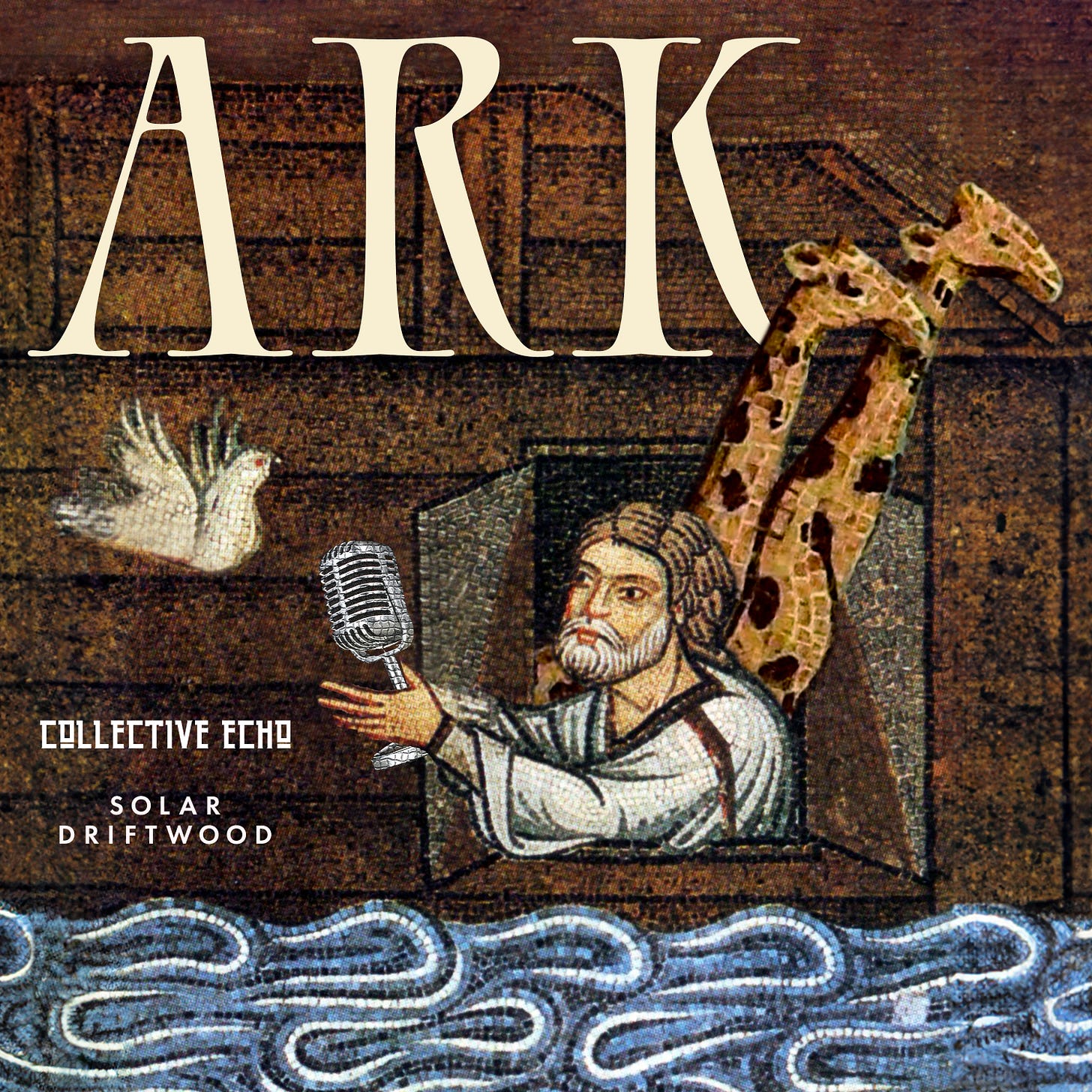

Speaking of making stuff up, our publisher has asked me to mention/promote this other project, so I will because I have to. It’s a new podcast called “Ark.”

Episode 1, “Beavers,” dropped this week. Here’s the trailer:

You can see why I, as a Makebelievian, endorse this project. Please check it out.

J. Finch Barlow

“Oooooooh, shots!” Moore screamed when he saw the bottle of Canadian Club.

“Would you like one, Roger?” Hume asked.

“No, Alan, I don’t drink whiskey straight like that. But yes, ok - why not? Actually, wait. Let me think about it for a minute. No. No, thank you. Yes, sure. No, I won’t, come to think of it. Well…yes, no thank you. OK, no.”

Moore took his suitcase to the bar cart and made himself a drink while the stunt crew walked through the mechanics of the ski jump. In the pre-credit opening scene—an essential part of every Bond movie—for “The Spy Who Loved Me,” Bond would be chased down the Austrian slopes by four armed KGB agents, evading them with backflips and returning fire with a ski pole rifle while skiing backward.

The chase would end with 007 skiing over an enormous cliff, his skis flying off his feet as he freefalls 3,000 feet to his certain death…until he deploys a Union Jack parachute and lives another day. The $500,000 scene ($2.7 million today) would be the most expensive single movie stunt ever filmed. Sylvester would be paid $30,000 if he could pull it off.

Since 1964’s “Thunderball,” producers had set a rule: no gin or vodka on Bond sets. The idea was to ensure the absence of Vespers, a cocktail considered bad luck for all Bond shoots. Filming “Thunderball” in the Bahamas, Sean Connery had downed seven Vespers before falling into a saltwater pool filled with the sharks used in some of the underwater action sequences. The producers still allowed whiskey.

Moore walked over to a table where Hume and Sylvester were mapping out the stunt. “Afternoon, Big Knit,” said Sylvester—a nickname Moore acquired for his work modeling sweaters in the 1950s.

Moore nodded, set a drink in front of each man and hoisted his own. “Good luck tomorrow, Ricky. I’m excited to see the final sequence.” He put a hand on Sylvester’s shoulder. “We’re all with you.” He raised his glass to the room, speaking up so everyone could hear. “Gentlemen, I know how much work you each do to make Bond and these films look fantastic. Here’s to you and your craft.”

Everyone drank what they had in stunned silence. Moore had never acknowledged anyone’s work but his own.

“You alright, Roger?” asked Hume. “Have a seat.”

“Today is my 49th birthday,” Moore said, shaking as he sat down. “I have one more year before my life is essentially over. So, no, I’m not alright.” He opened the suitcase and pulled out a bottle of Islay Scotch. “No one knows this, but I carry a bottle of Scotch with me when we’re shooting Bond. It helps remind me that Sean originated this character on film. He will always be the real 007. Anyone else who plays the character is a pretender to the throne.”

Sylvester was surprised by his growing pity for a movie start he disliked enormously. “Roger, this drink is fantastic,” he said, hoping to buoy Moore’s spirits. “What is it?”

“Oh, I don’t know,” Moore said. “I just poured a bunch of things I had into a glass and stirred.”

“Well, it’s excellent,” Hume said. “Why don’t we name it for you? In your honor. On your birthday.”

Moore looked up and gave the room a timid smile. “No,” he said. “Let’s name it for this place, where we discovered it as a crew. We’ll name it after the place where we all came together to film this historic stunt. And for England. Let’s call this drink the Bitmoore.”

Everyone looked awkwardly down at their shoes. “Or what about just Base Camp, Roger?” suggested Sylvester. “It’s more, uh, descriptive.”

“Excellent. You’ve all made me feel much better about being my own best friend. Now, will you help me with my comic one-liners for the remainder of the script? I have several I like. What do you think of this one? So, in the scene where I’ve just dispatched Sir William Klabbeg by pushing his wheelchair off the roof of a moving train in southern Estonia, I turn to Moneypenny and say, ‘So much for the training wheels.’ Or what about this one — in the scene where Bond has just escaped certain death by flying a blimp out of an Indonesian volcano, he turns to the camera and says, ‘Hot blimp, anyone?’ Oh, and this one: I’m in an underwater cave on Mars, and I say to the girl I’m scuba diving with, ‘Fancy a good Rogering?’”

Another awkward silence.

“What do you all think of those?” he asked, beaming.

Hume finally spoke up. “Roger, historically, improvising Bond’s lines hasn’t gone well for you with the directors of these films. And also, none of those characters or scenes you mentioned are in this movie or any other movie.”

“The directors?” Moore said, incredulous. “The directors?! I’m James fucking Bond, motherfucker!”

Another Editor’s Note: Fact-based cocktail historians claim the Base Camp was created at Attaboy in New York City by Matty Clark in 2017

SOURCES:

Albert R. Broccoli, Rules and Regulations for Actors Playing Bond Who Feel the Urge to Improvise Dialogue on My Goddamn Movies (London: Eon Books, 1984), p. 269

Roger Moore, I Found My Best Friend And That Friend Is My Best Friend (Me) (London: Jot & Tittle, 1986)

François Stikfigyur, “Vespers & Sharks: How I Saved the Drunkard Sean Connery From Sharks And Then He Punched Me In the Neck,” The Bangkok Post (May 13, 1968) p. B17

Contributors Notes:

Earl Thansonbeed’s novel, Itchy Face (Simpleton, 2000), was described in The Delano Journal of Wheat as “sort of like if you mixed words, sneezing, and a radical, immediate connection with God’s grace.” It was selected by the editors of Styptic as one of the top 100 greatest 20th-century books written in English about shaving. He divides his time between eastern Tennessee and southeastern Tennessee.

Actual For Real Credits:

Lee Adams, “It Was Do-Or-Die For The Ski Jump In The Spy Who Loved Me's Opening Stunt,” Slashfilm, 2022

Alan Hume, A Life Through the Lens: Memoirs of a Film Cameraman (Jefferson, NC: McFarland, 2004)