By Chandra Appletug

HOT SPRINGS, Ark. • 1930 — Greta Chang knew that if she ordered another shot of whiskey, she’d be ordering another after that. And then another.

“Another, Greta?”

Mac was already pouring. It was bootlegged and bad. Greta nodded her assent. Tomorrow was her day off anyway.

The regulars propping up the bar at the Loblolly Club at 2:30 most afternoons worked at one of the businesses on Bathhouse Row. They were helpers to the more senior bathhouse attendants. Or they were packers, wrapping patients in towels soaked in thermal water. Bathhouses were active in the mornings. In the afternoons, the workers hung around downtown Hot Springs gossiping about co-workers, complaining about bosses, laughing about patients.

Greta began spinning the shot glass slowly between her fingers as she took in this afternoon’s gathering at the Loblolly. Miriam Donk worked at the Hale Bathhouse cleaning tubs. William Brothersman folded towels at the Fordyce. Jimmy Fravolli tended the gardens at the federal venereal disease clinic. Millie Peters and Freda Hopkins washed dishes at the Ozark.

Diamondback

1½ ounces Rye

¾ ounces Applejack

¾ ounces Green Chartreuse

Stir with ice • Strain into a cocktail glass • Garnish with a cherry

Mac liked to keep Greta at the bar as long as he could. She held her liquor well. And among the Loblolly’s regulars, she was one of the better storytellers. When Greta was on a roll, the others stuck around. Bought more drinks.

Greta had worked at the Maurice Bathhouse & Spa for 20 years as a drainer. Her stories were filled with often disgusting details about the items she found during “draining hour” at the end of each shift. Her stories got better in the years right after Chicago mobsters started vacationing in Hot Springs and bottling moonshine just outside of town. Her best story was about an eyeball she found sucked into a vacuum pump. Not all Greta’s stories were about drains.

“Did I ever tell ya’ll the story about when I was a dental hygienist in Murfreesboro?” Greta asked. Freda Hopkins shook her head. “Haven’t heard that one, Greta,” William Brothersman said.

“Well, I was young and our neighbor was the town dentist, Dr. Zaterhousen,” she said. “My father sent me to work for him after school. One day—this was about 25 years ago—one day a farmer named John Huddleston walks into Dr. Zaterhousen’s office. The two of them had grown up together. Farmer Huddleston’s land was a couple miles south of town. People knew of it because the dirt was a greenish color. Some people said it was part of an old volcano crater.”

As Greta told her story, a tall man wearing a loose white robe walked into the bar, claimed a stool, laid a knapsack on the floor, and nodded to Mac. “Good to see you, Brother Bill,” Mac said as he poured the French monk a whiskey.

“So, Farmer Huddleston, he pulls a little bag from his pocket, shows it to Dr. Zaterhousen, and pours it out on a metal tray of dentist tools,” Greta continued. She paused for effect. Drank her whiskey. Motioned to Mac for another.

“Diamonds,” she finally said.

“What’d he want?” Jimmy Fravolli asked.

“Farmer Huddleston happened on the diamonds when he was digging up his radishes,” Greta said. “He told Dr. Zaterhousen that he wanted to hide them somewhere safe. Somewhere he could access them at all times. He said he wanted Dr. Zaterhousen to secure the diamonds to the back of his teeth.”

“He wanted what now?” Miriam Donk said.

Editor’s Note:

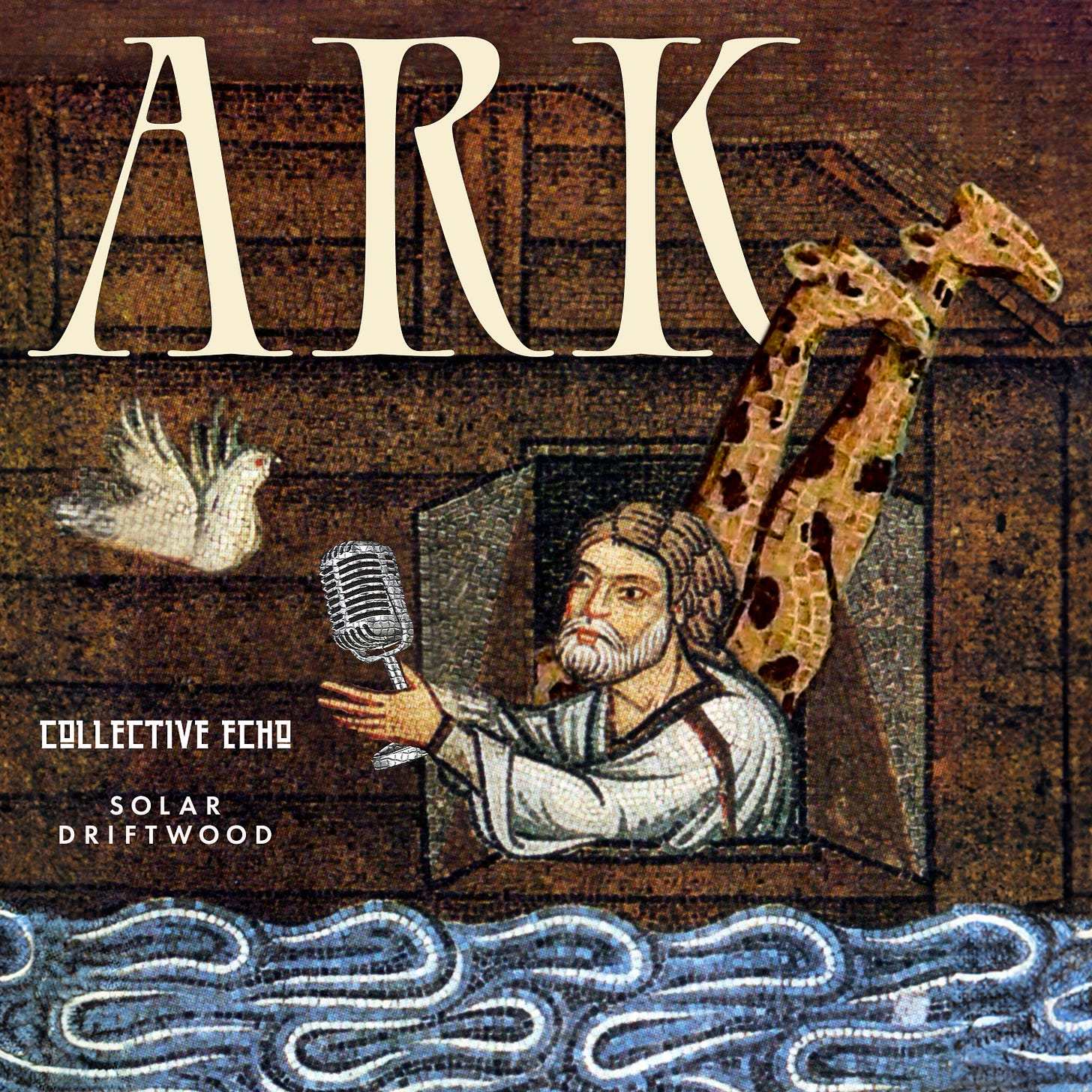

Our publisher has asked that we promote Episode 2 of his new show, called “Ark.” It’s an improvised comedy podcast revealing newly-found, ancient recordings of Noah and his wife Naamah interviewing animal couples aboard the Ark.

I realize, as a Makebelievian, I don’t have a lot of standing in this regard, but that premise for a podcast is just plain silly. Anyway, this episode purports to be Noah and his wife interviewing flying squirrels 5,000 years ago.

Please enjoy,

J. Finch Barlow

“Dr. Zaterhousen pointed out to Farmer Huddleston that it would look pretty damn cool if the diamonds were secured to the front of his teeth, but that’s not what Farmer Huddleston wanted. He wanted the diamonds hidden. So, Dr. Zaterhousen used dental epoxy to glue a diamond behind each of Farmer Huddleston’s teeth. But there were several diamonds remaining. The next day, Farmer Huddleston brought his wife Sarah in, and Dr. Zaterhousen glued the remaining diamonds to the back of her teeth.”

Brother Bill, whose real name was Guillaume the Carthusian, smiled. He’d heard Greta’s story before. In 1903, the French government expelled Brother Bill and his community from their monastery in France, where they’d survived by making and selling a liqueur called Chartreuse.

Ever since, Brother Bill had been practicing peregrinatio pro Christo, a medieval practice in which Christians voluntarily exiled themselves from their homeland, placing themselves in God’s hands as they wandered for Christ. In Brother Bill’s case, he wandered America, educating himself about the country’s drinking culture and sending reports back to his exiled Carthusian community. He also distributed bottles of Chartreuse to curious Americans.

A year after he’d fled France, Brother Bill found himself in southwest Arkansas, around the same time John Huddleston began uncovering diamonds on his volcano farm. So Brother Bill knew what was coming in Greta’s story. He also knew its ending would demand a special drink. As Greta concluded, he reached into his knapsack, withdrew a bottle of green liquid, and quietly placed it on the bar—making sure to keep the focus on Greta. He caught Mac’s eye and nodded.

“Soon, of course, Farmer Huddleston found more diamonds, which meant he needed more teeth to hide them,” Greta continued. “So, one by one, he brought his five daughters in to have Dr. Zaterhousen glue them gems to their teeth.

But then he ran out of children, so he made a deal with a couple of his farmer friends: If they let Farmer Huddleston glue his diamonds onto the backs of their teeth, in return, when Farmer Huddleston wanted access to his diamonds, he’d pay for Dr. Zaterhousen to rip all their teeth out and replace them with better-looking dentures. And, of course, they’d get to keep one of their original diamond-epoxied teeth as payment for their mouth rental. Within three months 87 citizens of Murfreesboro, Arkansas had mouths packed with diamonds.”

Millie Peters motioned for Mac to pour her and Freda Hopkins more whiskey.

“Dr. Zaterhousen was so happy,” said Greta. “All that epoxying and extracting and molding of new dentures. I had never met another dentist, but I was pretty sure I’d never meet a happier one in my life.”

Brother Bill, still smiling, pushed the bottle of green liquid across the bar. “Mac, will you fix us all a drink with your whiskey, the contents of this bottle, and a third ingredient of your choosing? The round is on me.”

“How about some apple brandy?” Mac said. “In honor of all those people in Murfreesboro who were never able to eat an apple again.” He poured the three liquors into a glass for each of his customers and handed them around the bar.

“And Greta,” said Brother Bill, smiling still because he knew the answer. “I don’t suppose you have any evidence proving this dental diamond drama really took place?”

Greta smiled, too. And while she did she pulled three teeth out of her mouth, shook them in her hand like dice, and rolled them down the bar toward Brother Bill. The monk stopped them with his left hand. When he lifted his hand, three enormous diamonds winked up at him. He laughed and hoisted his cocktail. Everyone else followed his lead.

“I got to keep three,” Greta said through her speckled smile. “Farmer Huddleston liked me because I got him super high on laughing gas sometimes.”

Another Editor’s Note: Fact-based cocktail historians claim the Diamondback was created at the Zig Zag Café in Seattle by Murray Stenson in the 2000s

SOURCES:

Priya Krystahl, “Fun With Liquid Crystalline Epoxy Nanocomposites, 1911 to 1957,” Arkansas Journal of Prosthetic Dentistry and Bed & Breakfast Guide, Little Rock Chamber of Commerce, 1996

Juliette Moreau, Sons of Bruno: 900 Years of Hard Partying in the Order of Carthusians, trans. R.P. Scadfsen (Grenoble: Èditions Fadaises,1984)

Rance Farnsworth Tiggle, “ Venereal Peril, Al Capone, and Communal Bathing: How Small Towns Attracted Tourists in 1920s America,” The United States Public Health Service Journal of Gross (Issue 36, 1941)

Contributors Notes:

As a lyricist, Chandra Appletug has received seven St. Kitts Sea Shanty Award nominations since 1987. Her shanty, “Hoist Hog-Eye Joe up the Main Yardarm,” was honored with the Captain Karl Squidge Memorial Plaque for Attention to Detail. When not working on her music, she likes to snort dry turkey tetrazzini soup mix and turn up the King Crimson.

Actual For Real Credits:

Attractions, Encyclopedia of Arkansas

Crater of Diamonds State Park History, Arkansas State Parks

Hot Springs, National Park Service

USPHS Venereal Disease Clinic, Encyclopedia of Arkansas