Editor’s Note: A quick thank you to Dubious Cocktail History subscribers: You’ve been through a lot in the last few months since inviting us Makebelievians to your inbox. We support you and are here for you. But actually, we won’t be here for you in May. It’s a tradition among scholars based in the Makebelievory school of history that every few months, we gather to recharge our batteries, grease our wheels, speak of the devil, let the cat out of the bag, put our cards on the table, and take the cake. We call this gathering The Replenishment, and this month, we are meeting in Tokyo to discuss the cocktail fauxrigin stories we have planned for you later this summer. (We also discuss idioms.) If you’re in town, stop by Cartwright Conference Room A/B at the Motel 6 Shinjuku. Our motto for this Replenishment, as it is for every Replenishment: Only by making up what didn’t actually happen can we hope to understand what might have. Please enjoy Mr. Pollasb’s not-real history of the Fog Cutter.

— J. Finch Barlow, Editor

By John P. Pollasb

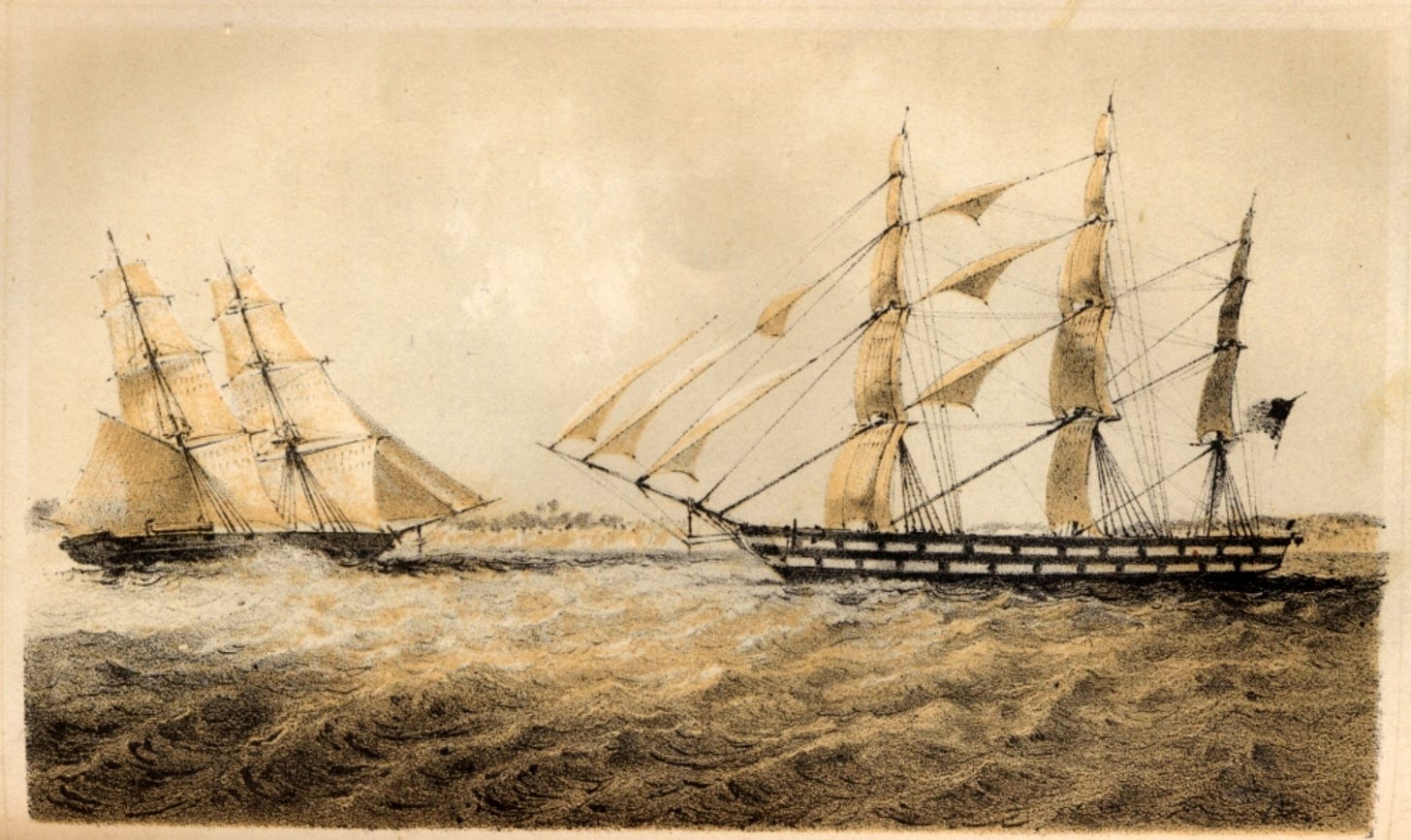

LAKE ONTARIO • 1853 — Gabriel Lokhausens could not have been more bored. As a crew member of a sailing cutter patrolling an enormous, cold, and misty lake, he was charged with looking for any water traffic attempting to bring goods into U.S. waters without paying tariffs. He was bored just thinking about how boring that was. Never mind that the crew hadn’t seen anything unusual or even mildly interesting since leaving their port in Oswego, New York two weeks earlier. Even the name of his naval organization bored him. The U.S. Revenue Marine Service. Who came up with that?

Soon after George Washington became president in 1789, Congress created the U.S. Revenue Marine as a “force to regulate the collection of duties imposed by law on the tonnage of ships or vessels, and on goods, wares, and merchandise imported into the United States.” Washington’s Treasury secretary, Alexander Hamilton, then ordered up a “system of cutters”—10 ships that would help a destitute new nation enforce its tax laws by patrolling the waters of the East Coast in search of smugglers—and revenue.

But 60 years later, that force—now more than double in size—was in tatters. Its crews had no uniforms. They’d gone years without pay increases or real training. Any weapons aboard the ships they provided themselves. Its captains were old, inept, and often drunk. Rations consisted of salted beef, old bread, vinegar, and water. And yet, most of the USRMS fleet—legendary sailing cutters like the RMS Vigilant and the RMS Stalwart—were at least seeing some action, chasing down pirate ships in the Atlantic and disrupting the illegal slave trade. Those ships were on “the constant hunt for pirates, plunderers, wreckers, and slavers,” as one (real) historian has written.

But the U.S. Treasury Department had long ago sent Lokhausens’s ship, the RMS Insignificant to the Great Lakes with a mission to corner fur trappers smuggling beaver pelts into New York. She was a tinpot of the Inland Seas. Captain Robert R. Shankstrop was the idiot at her wheel, and Lokhausens was one of her six miserable crew.

Fog Cutter

2 ounces light rum

1 ounce cognac

½ ounce gin

2 ounces lemon juice

1 ounce orange juice

½ ounce orgeat

Sherry

Mint

Shake all ingredients with ice • Strain into a tall glass filled with ice • Add a sherry float • Garnish with mint

Lokhausens and another enlisted man whose name Lokhausens couldn’t remember because it was so boring—Bob? Sam? Kieferleigh?—were balancing pencils by their erasers on the rail of the quarterdeck when suddenly a ship appeared out of the fog. She maneuvered next to the Insignificant and issued a distress signal. African men jumped from the ship into the water, yelling for help.

Captain Shankstrop, thinking they’d somehow come upon a slave ship, excitedly ordered his crew to help the African men clamber aboard. Just as they did, the other ship fired a heavy chain into the Insignificant’s rigging, rendering her mainsails worthless. The Africans who’d boarded the American ship pulled revolvers from their waistbands. One fired into the air. In a matter of four minutes, the Insignificant had been tricked and taken by pirates. Planks came down across both ships’ rails, and the Africans walked the Insignificant’s crew above the waves and onto their ship.

“Ahoy!”

The Americans looked up as a woman jumped from the crow’s nest and slid down the shrouds, holding a sword in one hand and a large mug in the other.

“I know no one really says, ‘Ahoy!’ but I think it’s funny,” she said. She was obviously the captain of this ship, and her crew obediently laughed along. Lokhausens couldn’t place her accent, but she was loud, and her eyes were bright.

“We saw you trying to balance pencils on the rail of your ship, so we knew you were either stupid or bored or both,” the captain said. “We also saw that your ship is very silly and that you have nothing good to steal and you are about as threatening as seven baby seals. We, too are bored, and also fairly drunk, so we thought ‘why not take that ship, just because?’ So we did. Have a drink.”

Men appeared from below decks with enormous mugs filled with ice and fruit and alcohol. They handed the drinks to the Americans.

“You are criminals!” said Captain Shankstrop. “The Revenue Marine Service, under powers granted by the United States Treasury Department, declares you under arrest.”

But Shankstrop’s men had already taken seats on the deck and were sipping their drinks.

“My name is Farfarbinjer,” said the woman, ignoring Shankstrop. “And now begins storytime.”

“Ooooh!” said Shankstrop, clapping his hands. He accepted a drink and sat down.

“Some of the details of this story came from a Spaniard named Francisco Lopez, who was captain of this ship when it was called the Nuestra Señora de las Nieves,” Farfarbinjer said. “Francisco Lopez no longer exists.

“We were forced onto this ship in Gallinhas,” she continued. “This is in Sierra Leone. More than 100 men, women and children under this deck, began sailing across the Atlantic. Near Havana, Francisco Lopez was caught by a ship that looked a little like your silly one. He turned north and escaped your water police—all the way up to the Gulf of St. Lawrence. He hid us there for some time. Many of us died. Those of us who were left sensed Francisco Lopez was afraid. So we planned.”

Farfarbinjer stopped abruptly and directed her gaze at Lokhausens. “Why are you not drinking, sausage face man?!”

“I finished mine, Captain, ma’am,” Lokhausens said, running his fingers along his forehead.

“Fill them up!” Farfarbinjer boomed. More drinks came up from below decks. “Where was I?”

“You were planning, Captain,” Shankstrop said. “In the Gulf of St. Lawrence.”

“YES!” Farfarbinjer yelled. Two startled Insignificant sailors who had just taken sips, dribbled their drinks out a little on their shirts. “Anyway, we killed that guy. We left the rest at the mouth of the St. Lawrence River guessing they would freeze and die. Then we sailed this ship up the river to this lake.”

“How long have you been on the lake, Captain ma’am?” Lokhausens asked.

“I don’t know,” Farfarbinjer said as one of her crew filled her mug. “Maybe hundreds of years. Maybe a couple of days. We have been stealing dead animal fur from ships and selling them to other ships. We also steal this horrible tasting liquid, but the almonds, fruits and mint we steal make it better. We don’t call this ship by its old name. We don’t call it anything.”

“Ah!” she said, pointing at her head like she’d remembered something important. “We need ice. We use a lot of it. When you see us—and you will not see us unless we want you to see us—and we are flying this flag, bring us ice.” The flag was red with a martini glass embroidered on it.

Shankstrop nodded. “Aye, Captain,” he said, taking the flag.

“You are the first people we’ve been bored enough to bring aboard,” Farfarbinjer said. “For this reason, you have the honor of naming this drink we’ve made you.”

“Captain Farfarbinjer, if I may,” Lokhausens said. “Your cutter came out of nowhere. It simply appeared out of the fog, and you took our ship so quickly. Perhaps the drink could be named in honor of this new ship that now belongs to you. The Fog Cutter.”

Farfarbinjer thought for a moment. Both crews were silent.

“No, that’s dumb and you’re dumb,” she said. “Well, maybe. Anyway, leave your mugs. Here are some to-go cups. We decided earlier that it would be fun to make you walk the plank. Remember, red flag equals ice. Go away.”

Editor’s Note: Fact-based cocktail historians claim the Fog Cutter was created by Victor Bergeron at Trader Vic’s in San Francisco by 1940 and first published in Bergeron’s 1946 Book of Food and Drink.

SOURCES:

Kristynne Krauft, Ahoy!: 19th Century Black Women Pirate Captains of the Great Lakes Region (Montreal: Shiver Me Co., 1972), pp 45-49

Gabriel Lokhausens, Bored Aboard: How I Survived The U.S. Revenue Marine Service With Just A Couple of Pencils and a Fine Sense of Balance (Oswego: U.S. Coast Guard History Press, 1899)

Admiral Phillip L. Conaughtiez, Insignificance: Why One U.S. Revenue Marine Service Cutter Was So Crap I Sent It To The Middle Of the Country (Annapolis: Rigmarole, 1860)

Contributors Notes:

John P. Pollasb lives in Marmon, New Mexico, where he is a poet, photographer, calligrapher, small-game warden, folklorist, asset-integrity consultant, peanut-butter sales associate, auguste clown, criminal defense attorney, line cook, nephrologist, and district superintendent for the United Methodist Church in the south-central jurisdiction. He was a recipient of the Cosgrove Shillfont Fraggle Biller-Fezz Poetry Prize for his collection “Sit Me Down in Your Rain Puddle of Grief, You Son of a Bitch.”

Actual For Real Credits:

Florence Kern, The United States Revenue Cutters in the Civil War (Washington: U.S. Government Publishing Office), 1988

National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior

U.S. Naval Institute

National Museum of the Great Lakes

I'll bet that guys name was Kieferleigh, it was quite popular back then.