By Staglore

NEW YORK • May 16, 1911 — “Right under the wire, Doc.” John D. Rockefeller raised his glass.

In return, Dr. John Shaw Billings, director of the New York Public Library, raised his glass toward Rockefeller’s. The other two men in the room—Edward Douglass White, Chief Justice of the U.S. Supreme Court, and William Howard Taft, 27th President of the United States—did the same.

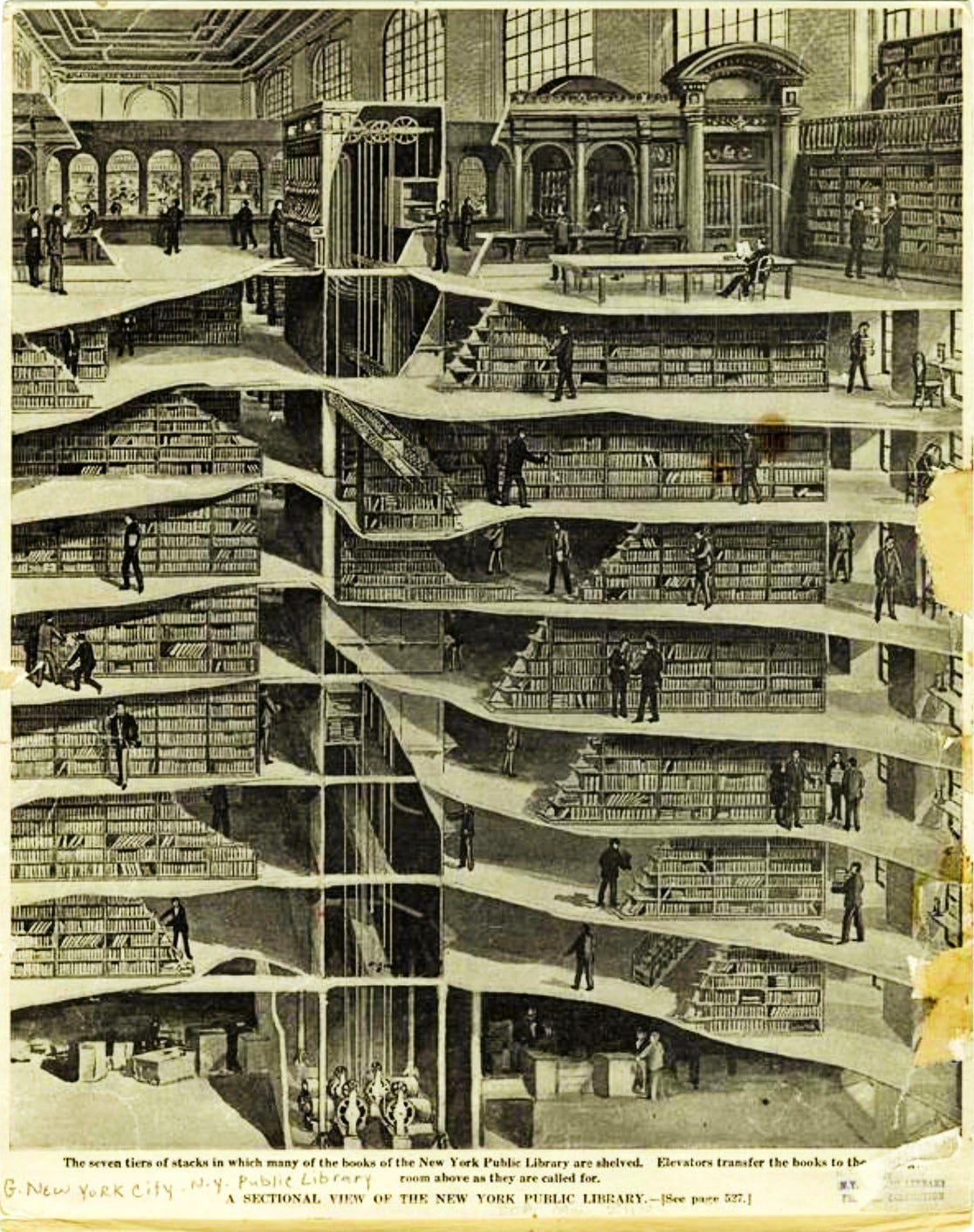

The men sat in a secret bar Billings had built—at Rockefeller’s request—behind a false bookcase on the library’s lowest subterranean level. In a little over a week, the library’s doors would open to the public for the first time, an eventuality that would have been impossible without a last-minute deal Billings had brokered among the four of them. It also wouldn’t have happened if Billings hadn’t saved White’s life a half-century earlier during the Civil War.

It had been 15 years since Billings sketched out the original Beaux-Arts design for the library on a cocktail napkin. He was now 73, a year older than Rockefeller, who had become a friend over the last decade. The two had bonded over twin loves: architecture and tequila. That friendship had resulted in enormous financial gifts from Rockefeller, the founder of Standard Oil, to the library.

Inside Job

1½ ounces of reposado tequila

½ ounce of Braulio amaro

½ ounce of sweet vermouth

½ ounce of Yellow Chartreuse

Stir ingredients in a mixing glass with ice • Strain into a rocks glass over a large ice cube • Garnish with orange peel

Billings had been one of the country’s most respected surgeons before he became one of its most respected librarians. He was also a world-class architect, and when a committee formed to build New York’s first truly public library, its members invited Billings to lead their effort.

But Billings was better at building, reading, and sewing people up than he was at accounting, and a few months before the library was set to open its doors he realized he’d spent the entire capital campaign on the building itself. Unless he found another source of funding, the most beautiful library on the planet would have no books, no staff, and no operating budget.

Billings turned to Rockefeller. He knew it would be a difficult request. His friend had already chipped in about one-third of the construction’s $9 million total ($280 million today). He took Rockefeller to the Hotel Astor for martinis.

“I’d love to help, Doc, but there are a lot of worthy projects around the city, and my foundation needs to spread these grants around,” Rockefeller said. He saw the panic on Billings’ face. “Ok, let’s do this: I’ll loan you $2 million, no payments due or interest accruing before the library’s Day One. But as soon as those doors open, you’ve got a year to pay me back and an interest rate of 33 percent.”

“John!” said Billings. He was sweating. “It’s a goddamn library.”

“OK, I’ll add another wrinkle,” Rockefeller said. “I own about 25% of my company. If you found a way to force the government to blow up Standard Oil into a bunch of little oil companies, I’d own proportionate shares of those. Get creative over the next three months. Make me the wealthiest man on the planet, and I’ll forgive the loan. If you can do it, I’ll throw in another $5 million as a founding endowment. Managed correctly, that should allow the library to exist without ever fundraising again.”

It was an absurd condition, but Billings was desperate, so he signed an agreement Rockefeller had scribbled on his cocktail napkin. He knew he'd be ruined if he didn’t raise the $2 million by the time the library opened.

But as Billings researched Standard Oil in the following weeks, a plan began forming. For years, journalists and oil business competitors had made the case that Standard, which controlled more than 90% of oil production in the country, was a monopoly. And they’d encouraged the courts to use new antitrust laws to do something about it. Standard’s attorneys had easily brushed away any small-time threats to the company’s anti-competitive stronghold. But Billings sensed the public mood was shifting and with Rockefeller’s covert encouragement, he made a visit to Washington.

The first stop was the White House, where he met with his cousin’s first uncle twice removed, President Taft. Billings explained his situation to Taft and told the president that while he couldn’t reveal how, if the government very quickly brought an antitrust case against Standard Oil he was optimistic it would win. Taking down Standard Oil would be an enormous political victory for the White House. Billings told Taft he would also waive any late fees on books the president borrowed from the New York Public Library for one year. Taft readily agreed.

Next, Billings stopped by the U.S. Supreme Court to visit its new chief, Edward White. The men had met in Louisiana after the seven-week Union siege of Port Hudson in the summer of 1863. White was an 18-year-old private, a bugler for the 12th Louisiana Artillery Battalion. The siege was horrific for the 7,000 surrounded Confederate troops. They ran out of medical supplies and food and resorted to eating rat and mule meat. White spent the last three weeks with a fever on a hospital cot but was so afraid of being captured that when his commanders finally surrendered Port Hudson, he left his bugle and ran into the woods.

Billings, a Union field surgeon, found White after the siege, dying in a ditch a half mile from the Mississippi River. Over several days, he nursed White to a point where the boy could eat, and finally stand. When he felt White was strong enough, Billings walked him for a week, 100 miles south along the river to New Orleans. The city, which had been taken by the U.S. Army, was where White’s mother lived. White was alive, but he was now a Confederate deserter living in Union territory. He remained there for the rest of the war, and never spoke about his wartime experience as his post-war legal career blossomed.

“Hello, Dr. Billings,” White said when Billings walked into his Supreme Court chamber.

“Hi, Eddie,” Billings said. The men hugged. “I need a favor.”

“Anything,” White said. “But write it down. Here, on this cocktail napkin.”

Days later, Taft brought its case against Standard Oil, which quickly rose to the Supreme Court’s docket. On May 15, 1911, the high court ruled that the company was indeed a monopoly and broke it up into more than 30 smaller companies. White wrote the majority opinion, which was hailed as brilliant and the epitome of legal humility, coming from a conservative, business-friendly justice. The stroke of White’s pen on the opinion gave Taft more political leeway, secured Billings’ place in library history, and doubled Rockefeller’s wealth.

A day later, as the four men gathered in the library’s secret basement bar, the world's first billionaire ($31 billion today) was in a great mood. He mixed the group a new tequila drink he’d created with Italian amaro, fortified wine, and a yellow French liqueur.

“What are we drinking, John?” Billings asked Rockefeller as they toasted their success.

“Let’s call it the Inside Job.”

Editor’s Note: Fact-based cocktail historians claim the Inside Job was created at Attaboy in New York City by Zac Pease in 2017.

SOURCES:

Chammie S. Krumps, “Circle Stains: The Preeminent Role of Cocktail Napkins in Critical Junctures of Human History,” (PhD diss, University of West Tuscaloosa), p. 36

Edward Douglass White, Racist, and U.S. Supreme Court Justice: That’s Me! (New York: Crayon & Co, 1920)

Contributors Notes:

Staglore is a performance artist who recently received a two-year commission from the U.S. State Department to produce a 40-minute operetta illustrating the Office of International Energy and Commodity Policy’s permit application process for cross-border natural gas pipelines. Two Saturdays each month he performs as Poopies the Clown for potty training-resistant children.

Actual For Real Credits:

“History of The New York Public Library,” The New York Public Library

Natalie Burclaff, “Rockefeller: Making of a Billionaire,” Library of Congress

“Port Hudson,” American Battlefield Trust

Andrew Kent, “The Rebel Soldier Who Became Chief Justice of the United States: The Civil War and its Legacy for Edward Douglass White of Louisiana,” American Journal of Legal History, Volume 56, Issue 2, June 2016, Pages 209–264

Next week: Fog Cutter • A U.S. Coast Guard crew patrolling Lake Ontario discovers a tiki original