By Joan Crispee Tille

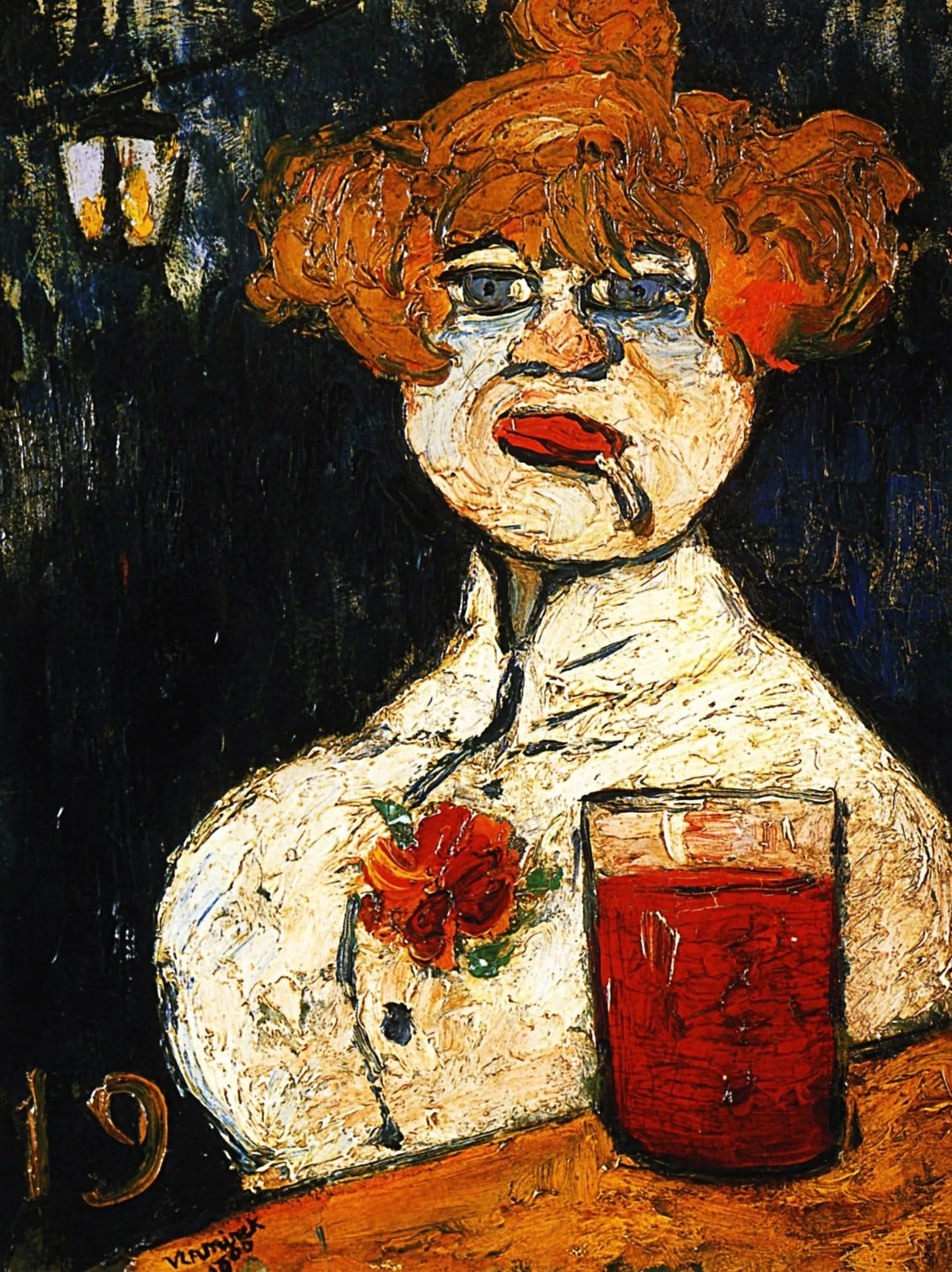

PARIS • 1900 — Pablo Picasso and Carlos Casagemas had been sitting with the Mexican artist Paloma Suárez at Le Rat Mort for two hours when the painter Maurice de Vlaminck walked in, kissed Suárez, and sat down at their table.

“Who are you?” Vlaminck said, nodding toward Picasso and Casagemas as he poured himself a glass of wine from the bottle in the middle of the table.

“These are my friends Pablo and Carlos,” Suárez said. “Be nice. They just arrived from Barcelona on Tuesday. Pablo has a painting in the Exposition Universelle.”

“You are a painter!” Vlaminck said, taking a cigarette from the pack on the table.

“We are both painters,” said Casagemas. “Pablo is better. He also gets all the women and magazine assignments.”

“Carlos is just shy,” said Picasso. “It is true, though, that we are here so I can write about the exposition for an art magazine in our country called Cataluaya. It is our first time in this city.”

“Welcome to France, then,” Vlaminck said. “Another bottle so that we four painters can talk paint!”

Paloma

½ lime

2 ounces grapefruit soda

2 ounces of tequila

Pinch of salt

Squeeze lime into a Collins glass • Add lime shell, tequila and salt • Add ice and soda • Stir

It was a heady time to be a painter in Paris. The Exposition Universelle, or World’s Fair, had brought artists from around the world to the city. Athletes, too, had come to the French capital for the second staging of the modern Olympic games.

Four years earlier, in Athens, Paris had won the right to host the Olympics. But because of their political and financial clout, the city’s World Fair officials were able to block Olympics officials from organizing a competing event. They could not, of course, actually prevent people from participating in games and sports, so wily Olympic officials organized a stealth Olympic games in Paris that lasted five months, often surreptitiously within officially sanctioned World’s Fair events.

Paris Olympic Committee members deputized underground referees, judges, and umpires to enforce rules and declare winners in sports such as swimming, tennis, sailing, rowing, rugby, cycling, and gymnastics. Many Olympians had no idea they were participating in the games until they were handed a medal. The tennis players, for example, merely thought they were engaging in a match between friends.

Over the course of the summer and into fall, as Parisians learned through word of mouth that the Olympics were indeed taking place in their city, other non-traditional sports were spontaneously added to the Olympics roster. The Olympic Committee sanctioned some of these Olympic sports retroactively. Ballooning, croquet, and fishing appeared only at the Paris 1900 games, and their medal winners were registered only that one year.

The committee denied medals to the winners of some of these imprévu, or “unforseen,” sports, though winners received a certificate of citation commending their “unusual athletic ingenuity.” Citations were given in sports such as:

Candle Placement

Spot the Pale Stag in the Tapestry

Weariness

Ring Around the Pickpocket

Casual Crying

Sitting Upon Fruits

Stockings

Slap the elephant (at the Parc Zoologique de Paris)

Funeral

Eyes Closest Together

Examine the Hog’s Tongue

Laugh at the Old Fish Cart Driver

Pumpkin

Walk About the Vicarage

Engraving with the Local Magistrate

Catch the Fat Fowl

Brute

Toss the Handkerchief Into the Old Vase

The absinthe had come out at Le Rat Mort, and Casagemas was passed out on the floor. The volume of the argument between Picasso and Vlaminck had increased over the last hour. Picasso was 19 and obsessed with Toulouse-Lautrec’s use of color. But he had already been thinking about form and had decided to take the opposite view of whatever Vlamicnk had to say. Vlaminck was 24 and would soon become a key member of les Fauves known for their bold use of intense color.

“Unthinking use of color is lazy and boring,” Picasso finally said. “And you are boring me, Maurice.”

Vlaminck calmly drank to the bottom of this absinthe, then reached across the table and slapped Picasso across the face. “Was that boring, you filthy Spaniard?” said Vlaminck.

Picasso stood up from his chair, wobbled, caught himself against the wall, and then swung a slap at Vlaminck’s face, missing him by two feet and knocking his drink to the floor. Suárez backed away from the table, took out a small notebook, and began taking notes. Picasso righted himself, launched at Vlaminck with his left hand open and slapped the Frenchman across the jaw. The smack sounded across the bar. Other drunk patrons circled around the two painters, cheering.

For 20 minutes, Picasso and Vlaminck slapped one another with varying levels of success. Suárez then separated them, guiding them each to a seat and ordering each a glass of tequila and grapefruit soda – a concoction she’d once had in her home state of Jalisco that she said would help revive them. As soon as she saw they were both finished with the drink, she banged a spoon against a glass and yelled, “Commence slapping!” The two men lurched toward one another, open-handed and swinging.

After another 20 minutes, Vlaminck was on the floor, vomiting in a corner. Picasso’s right eye was swollen shut and he had lacerations across his right cheek from a ring on Vlaminck’s hand that he’d turned palm-forward (3 point deduction). Inspecting the scene, Suárez helped Picasso up from his chair and raised his right arm.

“The gold medal winner of the definitely official Olympic sport of A Good Slapping is Spain’s Pablo Picasso!”

Blood ran into Picasso’s mouth as he smiled. His friend Casamegas had missed the whole thing, but it had been Picasso’s favorite night yet in Paris. As Suárez held his arm in the air, he made two decisions. The first was that he would make this city his home.

“Thank you for welcoming me to Paris,” he said to Suárez. “For declaring me an Olympic champion slapper, I will one day name my youngest daughter for you.”

Editor’s Note: Fact-based cocktail historians claim the Paloma was created in 1950 when a brochure for Squirt suggested mixing it with tequila

SOURCES:

Jennifer Le Droig, SMACK!: From Aristotle vs Plato to Zola vs Turgenev—History's Greatest Slapfights and the Food They Ate Afterward—With Recipes (New York: F.R. Jasper Company, 1998)

Christian Skanque, “Very Awful Sports of the Olympic Games,” (Ph.D. diss, Nelsonville College University), pp 56-98

Contributors Notes:

Joan Crispee Tille’s most recent CD, a compilation of carillon chimes called “Violate the Hog Line,” was released in January 2013 to tremendous critical acclaim. Between 1974 and 1992, Tille took a notation each time she fell down. The collected log, “Down” (Calf Creek Zipperman), won the 1997 Pardon Low Johnston Prize for Handsome Jottings.

An excellent missive and cocktail. I’ve actually been lobbying to get Funereal into the official games for the last 20 years or so and remain optimistic